For the last couple of summers, Nancy has been working hard to ‘branch out’ with a larger selection of (native) butterfly host and nectar plants around the yard to bring a greater variety of butterflies to the neighborhood. It is starting to pay off. Besides our Monarchs, we’ve seen more Zebra Heliconiansinfo (our state butterfly, formerly known as the zebra longwing). We’ve seen Polydamas and Giant Swallowtails. We’ve also seen one of the Duskywings (the Zarucco, I think), a few Sulphurs, and even some Atalas. And we’ve recently seen chrysalises of the Atalas and then the Giant Swallowtails. Earlier this month, I expanded our explanation of the Atala Butterfly life cycle on that page of our website (www.BeeHappyGraphics.com/gallery/atala.html). Now I’m going to tell you a few things about the life cycle of a Giant Swallowtail Butterfly.

The Egg

For this discussion, we will start with a single, 1 to 1.5 millimeter (just under 1/16“) cream to brown colored egg with orange secretions, on the upper surface of a leaf. It is laid on its host plants, members of the citrus family. In this case, that’s wild lime. The egg lasts four to ten days before hatching, depending on the temperature and host plant.

The Caterpillar

The larva (a.k.a. caterpillar) then goes through five instars (periods between molts). Unlike the Monarch Butterfly instars, all five look different. The first instar has hairs. The next instars have been compared to bird poop. The younger instars are more realistic-looking as bird droppings with more contrast than the later instars (shown in Figure 2). They rest on top of the leaf and are nocturnal. That makes sense – being seen moving around during the day could blow their disguise. The more mature instars rest on the stems and have been theorized to resemble small snakeheads. These caterpillars also have a red, antenna-like osmeterium, which is not usually visible (and which we have not yet seen).

Update (3/2/2023)

Joanne Miale, a reader in Southern California, was kind enough to provide the following two photographs. They help fill in the gap between the caterpillar on the left side of the branch in what is now Figure 4 and the chrysalis on the right side. Her too-small lemon tree attracted these butterflies. As the resulting larva grew, she collected the more mature larva, along with food, hoping to relocate the caterpillar to a larger tree with a better food source and protection. She didn’t expect it to pupate in the container.

The osmeterium is shown in Figure 2. In Figure 3, the larva has just tied its tail to the branch and made its silk harness, but the pupa hasn’t yet emerged.

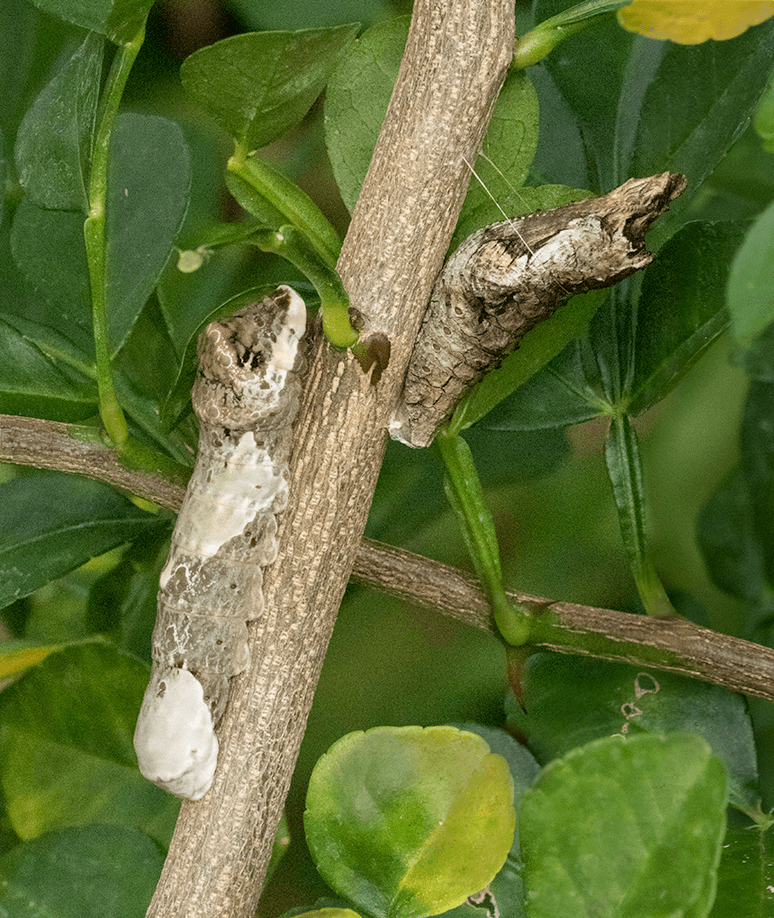

The Chrysalis

After three or four weeks, when it reaches a length of about two inches (5 cm), the larva will pupate. It could form the chrysalis (not to be confused with a ‘cacoon,’ which is just an outer protective cover spun by a moth larvae for their chrysalis) right on the stem of the host plant, or it could travel a short distance to a vertical surface. This differs from the Monarchlife cycle, which because its host plant is an easily devourable species of milkweed, must travel up to twenty feet to find a safe place to pupate. It also differs from the Atala, for which all sibling larvae pupate together on their host plant. That means they don’t have to worry about their slower-developing siblings coming by and eating the leaves around them, making them fall to the ground.

As seen in the above picture, the chrysalis hangs tail-down at an angle of about 45° to the structure with its top suspended from silken threads. The pupa (a more general name for chrysalis that can be also applied to all metamorphizing insects, not just butterflies and moths) will last from ten to more than twelve days before emerging into an adult. Unlike the Monarch, we have not noticed the Giant Swallowtail chrysalis changing color over time.

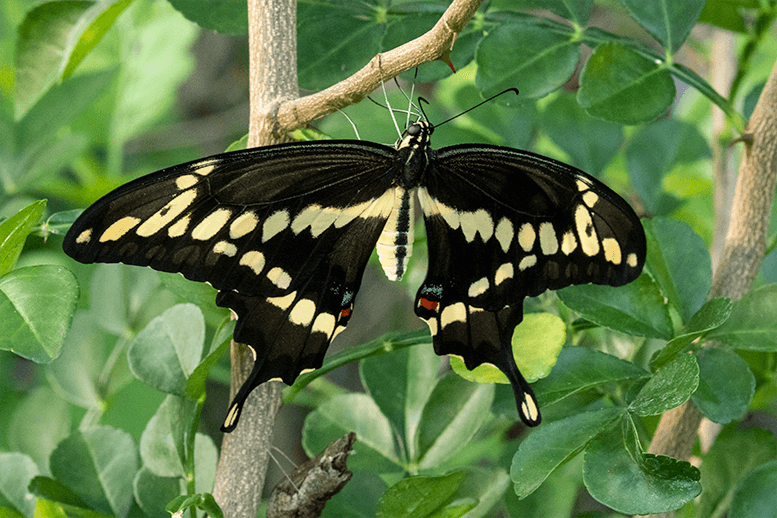

The Adult

As shown in Figure 3, the adult is black with yellow trim on the top, and could possibly be confused with other black-and-yellow swallowtails like the Black Swallowtaildescribed (and very-rarely-seen species like the Schaus’described and Bahaman Swallowtailsdescribed). The underside of this butterfly (not shown (yet)) is predominantly light yellow. The adult lives six to fourteen days. This butterfly lives in the near-coastal areas from Florida through the Carolinas (compared to the Black Swallowtail, which extends north just beyond Massachusetts).

Epilogue

Nancy took all of the pictures shown in the original article and Joanne Miale contributed Figures 2 & 3. As you noticed, we haven’t yet photographically documented the entire life cycle of this butterfly. And I don’t know when Nancy will be satisfied enough with her pictures to add an image of the Giant Swallowtail to our commercial collection. We’ll just have to wait and see.

Besides our personal experience, we have relied on a number of resources, including University of Florida Entomology and Nematology Department and Butterflies of the East Coast: an observer’s guide by Rick Cech and Guy Tudor, as well as the links highlighted throughout the article.

Leave a Reply